Managing New Product Development

Published January 19, 2015

Use a New Product- or Service-Introduction Strategy Map

There is a lot of pressure to introduce new products as a brewery is building a product portfolio. This is especially true in the craft brewery business, where brand community members expect something special to emerge on a pretty regular basis. We will discuss elsewhere the idea of having a “train schedule” for new product and service introductions that matches the rhythm of the markets. Here I describe some basic gospel for risk management of new product introductions. New product introductions must be done in an organized and strategic way, so that you minimize your risks, and don’t get in over your head. We highly recommend that mangers use a visual map to help keep their product/project portfolios and risk levels organized and explicit.

Two Key Risk Variables: Technological Capability & Know-how and Market Capability & Know-how

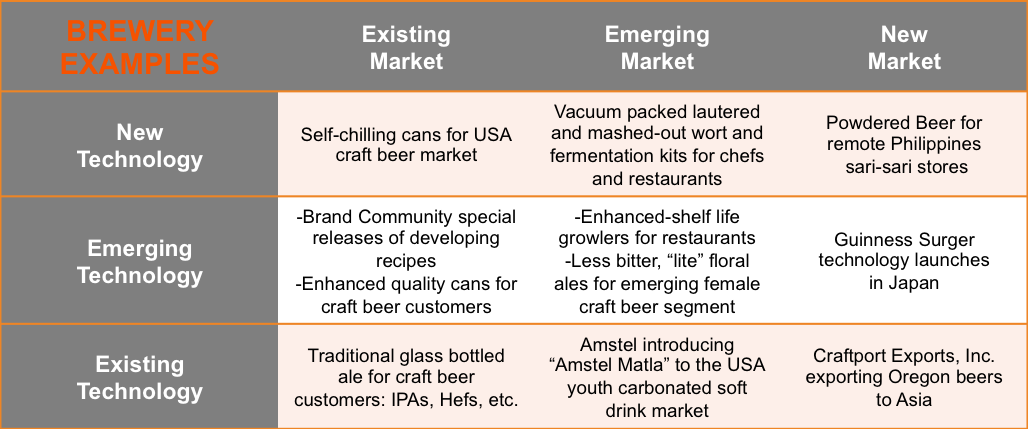

The table below gives some examples of product projects mapped against two critical risk/reward variables. On the vertical axis is experience, capability and know-how with the necessary technology. For the purposes of this strategic exercise, "technology" should be understood pretty loosely as something like: “any tool to do work to help you convert one thing into another.” A tool can be physical hardware like bottles and cans, or non-physical software, like computer programs, rational theories and logical processes (math and statistics, for example). This means that recipes can fit on this map as technology just like grain mills and kegs. (In our application of resource-based strategy at CAS, we usually categorize recipes as a knowledge resource rather than a technological resource). The other axis rates marketing capability and know-how with the intended market or market segment(s). Markets and market segments are groups of customers clustered by some demographic or other discerning characteristic: location, age, gender, taste preference, diet preference or restriction, urban, rural, nation, culture, industry and so forth.

This main idea is relatively simple: the lowest risk innovations and introductions are targeted at a market that you know well, using technology and processes that you know well. The highest risk innovations and introductions are targeted at new markets that you don’t really know yet, using new technology and processes.

The best average returns across projects (controlling for the level of risk) tend to come from innovations and new product introductions that either: a) target an emerging market using existing technology and processes, or b) use emerging technology and processes to target an existing / known market. Slightly more risky is targeting a brand new market with existing technology and processes, or using a brand new unproven technology or process to target and existing market. Providing existing technology to existing markets is low risk, because you have strong knowledge of both. Unfortunately, most of the time, lots of others in the business have that knowledge and those capabilities as well, so competition tends to be strong, limiting the ability of these projects to yield “abnormal returns.” Abnormal returns are those that are out of sync with normal or average industry returns (profits). In the case where the technology and the market are both well known to you, but not to others, then you have a strong source of competitive advantage, and might very well be able to gain abnormal returns until enough others imitate and drive the margins down. It's standard VRIO thinking.

Example: existing market, emerging technology. Your existing brand community members typically want something new and different – so you release special one-off limited production recipes you are working on (emerging technology), offering limited releases from time to time to these loyal customers (existing market). Because you know they are critical to your business model, you plan ahead to provide these existing market, emerging technology products. It may be costly and inefficient, but your community members love them and the value returned to your brand more than makes up for the relatively low revenue and cash margins generated from these products. You realize this and can plan ahead.

Example: emerging market, emerging technology. Mini kegs and growlers are emerging technologies that are still improving in design to maintain freshness and shelf life, and they are getting more popular within the existing craft beer market. A great example comes from Growlerwerks.com and their U-keg pressurized growler. Perhaps there is a new market for these packages, Restaurant sales. Distributors could be delivering growlers instead of kegs, and restaurants selling a growler instead of a pitcher might work around valuable hard to acquire tap-handle space at the bar. This allows the restaurant to provide more choices, gives craft beer suppliers new advertising real estate (the side of the growler) and allows the customer to take home the leftover instead of over-drinking. An interesting value proposition all around.

The key to being profitable when introducing new products is that, for each new product introduction, one of these critical dimensions should almost always be grounded as well known, well understood, and existing. Once you get into the realm of targeting new markets with new technologies, all bets are off. This is a very complex and difficult endeavor. Certainly there is a time and a place for taking a big risk and targeting a brand new market using emerging or new technologies and processes, but this certainly should not be your modus operandi.

Set a Standard and Track Performance

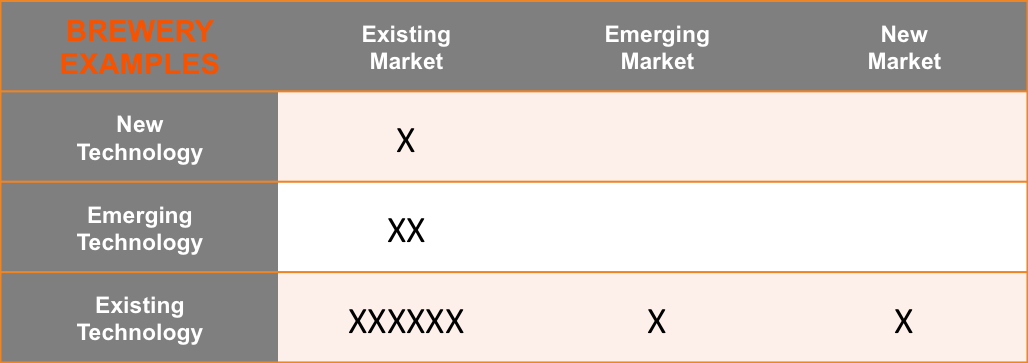

A good portfolio of R&D projects will be weighted sensibly. This means that the largest percentage of projects will involve existing technology and your existing market. There will be progressively less and less projects as you get farther away from having one or both of the dimensions grounded in past experience and expertise. The table (below) shows a decently balanced portfolio of R&D projects over the course of time.

In order to keep your product development and introduction and portfolio build-out moving and organized, set a standard for each category. For example, a small craft brewery might find it can handle well a portfolio of:

-Six different tried and true recipes produced and sold to the existing market.

-Two one off projects: one special release recipe for the brand community, and one trial with a new package.

-One research project learning about new brewing/distribution technologies.

-One introduction of an existing portfolio item to an emerging market

-One research and development project about a completely new market.

At any given time, a brewery’s ownership, management and leadership should know every project/program and how it is doing. A map on the wall works just fine. Furthermore, the performance of all the items in your mix, both current and historical, should be tracked carefully to find out if there are categories of projects with which your team has particular success or which tend to lead to nowhere. Items to keep track of: time to market, cost of program, attention-time, emotional resources expended and gained, revenue of project and return or profitability of project. This way, you can balance your portfolio to match your strengths and to pursue things that are emotionally rewarding rather than draining. For example, one craft brewery might find that they are much better at the marketing side than at the technology side of the business, and enjoy the experience more, while another may find just the opposite.