Recent Blog Posts

- Is 2021 The Most Important Year Ever For Your Brewery To Win A Medal?

- Creating New Demand In 2021 and Beyond

- What Does Sweetwater Brewing Company’s Sale Mean For Most Small Breweries?

- A Helping Hand For Cash Strapped Breweries

- Has Craft Beer Flavor Innovation Played Itself Out?

- Brewery Staff Attire

- Craft beer is NOT depressed, but the Brewers Association may be...

- Nailing the Basics: Inventory for a Brewery

- Has the BA Become Too Big to Succeed?

- Making Sense of the Revised Craft Brewer Definition

- Two Weeks That Changed My Brewery's Strategy

- Don't Get Stuck in the Middle: European Ownership, Flagship Strategies, & Craft Beer Market Growth

- Goodwill Can Be an Asset for Your Brewery

- Update on Craft Beer in Australia

- 12 NW Whiskeys Reviewed

Submitted by

SUBMITTED BY Sam Holloway ON Tue, 04/22/2014 - 17:31

Sam Holloway, Ph.D. – Crafting A Strategy

Apologies to Patrick Henry…I just returned from a great week in Denver and the 2014 Craft Brewer’s Conference. It was great to reconnect with old friends, meet new ones and attend some great sessions. One session in particular, “Surviving Rotating Handles” really struck a nerve for me. Congrats and thanks to E3 Craft Strategies’ Marty Ochs for putting together a talented and spirited panel.

For those of us at the panel, we saw some passionate folks who fundamentally disagree on the future. Marty constructed a panel representing the traditional 3-tiered system: Representing breweries was a great brewery co-founder from Elevation Beer Co., Xandy Bustamante. Representing distributors was an old-school brand manager from Philadelphia, Tom Buonanno from Muller, Inc. distribution. And perhaps the most passionate of them all, representing retail was Scott Blair, proprietor of Hamilton’s Tavern in San Diego. What an awesome crew to highlight an impending problem facing the craft beer industry. – Brewers and consumers want variety, but distributors want more sameness. More sameness is more profitable, could chasing profits result in the death of distribution, as we know it?

At Crafting A Strategy, we are business professors who studied many different industries before finding our true love in craft beer. I want this blog to focus in on the role of the distributor – or rather the distributor business model – to explain that distributors may need to wake up and reinvent their business model to survive (Johnson, Christensen, & Kagermann, 2008). Why would this cash cow of a business need to change? Eastman Kodak, Bethlehem Steel, Woolworth’s Department Stores… any of these companies ring a bell?

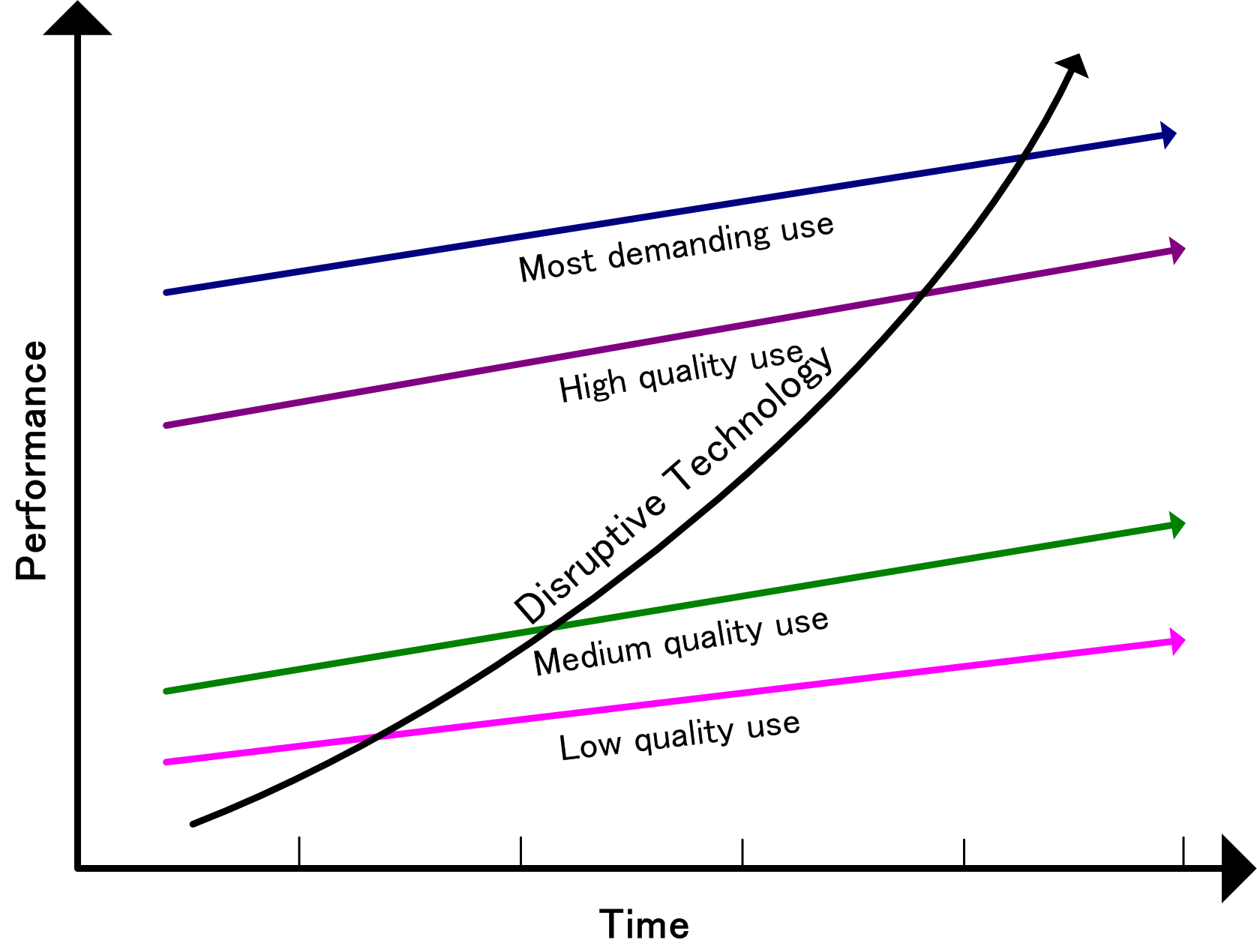

Clay Christensen and Michael Raynor (2003), have a wonderful book, The Innovators Solution, that shows how leading companies follow the profits to their ultimate demise. Chapter 2 – How Can We Beat Our Most Powerful Competitors, details a particularly important phenomenon, which they term “Fleeing up-market.” This process occurs within an industry’s most powerful firms, when these powerful firms chase short-term profitability found in their traditional business model, and ignore disruptive technologies and processes found in the business models of new entrants. Here’s an example from the steel industry (adapted from Christensen and Raynor, 2003).

Bethlehem Steel, U.S. Steel, remember the dominance of these large, integrated steel mills? Even the Pittsburgh Steelers NFL team celebrates this business model. They had incredible barriers to entry[1], because the only way to manufacture high quality steel was to own large deposits of iron ore. If you own all the good land, no new competitors can get this critical input and thus, you have a dominant market position. How could new entrants get around this barrier to entry? A new entrant, NUCOR Steel, found a way to recycle scrap steel and thus gain the critical input without owning large deposits of iron ore. This new business model was termed “Minimills” because they could be much smaller and more efficient than traditional steel mills that were doing things the old way (Christensen & Raynor, 2003). The only problem, minimill processes were initially crude, and they could only make the most basic and least profitable kind of structural steel, rebar (see chart below). So, what did Bethlehem Steel and the large integrated steel mills do when this new technology for steel production threatened their very livelihood? They let NUCOR have all the rebar – its margins are the lowest and least profitable – and they kept going along as if NUCOR had done them a favor. Imagine the conversation in the boardroom: Bethlehem CEO, “Don’t worry about minimills like NUCOR, their process is crude, they will never be able to make structural steel or sheet steel, just give them the rebar and let us redeploy all of our resources into the higher margin stuff. They are doing us a favor!” In the back of his mind, the Bethlehem CEO may have said, “Since my bonus is tied to share price, and I plan to retire in two years anyway, this strategy will also maximize my retirement, a win-win!” Guess what, Wal-Mart entered in hardware and Woolworth’s let them have it. Fujifilm, Canon, Sony and Nikon entered in digital cameras, and Eastman Kodak let them have it. Sticking with Steel for now, see Christensen’s chart below as to how this decision to “let the new entrants have it” and flee up-market without changing the business model led to incredible profitability, for a few years. Ultimately, NUCOR refined and improved their processes, and was able to make all of the products in the steel industry, cheaper, faster, and at the same or better quality. Bethlehem fled up-market until they were dead firm walking! Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy in October 2001.

Caption: Generic Pattern of Disruption as Incumbent Firms “Flee Upmarket”Source: Image courtesy of Magpixie under Public Domain

So now, back to the Marty Ochs’ panel at the 2014 CBC. Distributors are the kings of the castle. Better capitalized, better efficiency, more and better relationships, they seem unbeatable. But on either side of them in the 3-tiered system are partners screaming for a different business model. Rotating handles, variety, appealing to consumer tastes, lower profitability…the brewers and retailers are innovative, looking for a better way, and always told to just keep things the same and it will be better for all of us. Why so resistant to change? I mean, these distributors have been around much longer than craft breweries. Bright, successful people run them. They have better experience and way more information – how many of us small craft breweries can afford Symphony IRI data, after all. How can distributors fail?

Distributors rely upon market research for decision-making – many use IRI data. The fundamental assumption of market research is that the past is a good predictor of the future. Has your distributor ever suggested to you that you go into six-pac glass instead of aluminum cans “because the data shows 96% of all six-pacs are in glass”? What if Oskar Blues had listened to the past instead of forging their own future in cans? Retailers, brewers, and consumers care about variety and are trying to create a future of rotating handles where there previously was no market. There is no past, no market research that they can rely upon to ‘research’ how the rotating tap market might look. Market research is useless to them… But they are forging ahead anyways because they believe variety and choices among quality products is the right thing to do…so what will the future look like?

Something has to give. If Christensen and Raynor (2003) are correct, maybe the rotating handles phenomenon is the rebar of the craft beer industry. Existing distributors will ignore the market demand, let someone else gain a foothold in the market and leverage their sunk costs in existing trucks and warehousing practices, to reap the immediate profits, right into their own demise. A new entrant, with a passion for variety and an understanding of the needs of places like Elevation and Hamilton’s, may bring new technologies and processes to market, perhaps a cleverly designed truck technology – that automatically delivers 1/6th bbl kegs and gathers empties using a conveyor system. Will current distributors continue to ignore these changes in consumer tastes? I sure hope not, but with 10,000 breweries by 2020, the business model of distribution better get ready for change.

References

Christensen, C. M. & Raynor, M. E. 2003. The innovator's solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth: Harvard Business Press.

Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., & Kagermann, H. 2008. Reinventing Your Business Model. Harvard Business Review, 86(12): 50-+.

[1] For more on barriers to entry, members can view our white paper, “Threat of New Entrants”