Recent Blog Posts

- Is 2021 The Most Important Year Ever For Your Brewery To Win A Medal?

- Creating New Demand In 2021 and Beyond

- What Does Sweetwater Brewing Company’s Sale Mean For Most Small Breweries?

- A Helping Hand For Cash Strapped Breweries

- Has Craft Beer Flavor Innovation Played Itself Out?

- Brewery Staff Attire

- Craft beer is NOT depressed, but the Brewers Association may be...

- Nailing the Basics: Inventory for a Brewery

- Has the BA Become Too Big to Succeed?

- Making Sense of the Revised Craft Brewer Definition

- Two Weeks That Changed My Brewery's Strategy

- Don't Get Stuck in the Middle: European Ownership, Flagship Strategies, & Craft Beer Market Growth

- Goodwill Can Be an Asset for Your Brewery

- Update on Craft Beer in Australia

- 12 NW Whiskeys Reviewed

Submitted by

SUBMITTED BY Mark Meckler ON Mon, 10/15/2018 - 18:15

By Mark R. Meckler, Ph.D. and Sam Holloway, Ph.D., October 16, 2018

We’ve been scratching our heads at the growth strategies of some of the USA’s iconic (formerly) craft breweries. While the vast majority of regional craft breweries are experiencing flat to negative growth, a small handful of corporate owned/invested craft breweries are expanding. At first glance, it seems like these growing regionals may be doing something ill advised and perhaps going about growth the wrong way. As we pondered this phenomenon, we understood that this corporate craft strategy was neither unwise nor folly, and that it is a warning shot to all craft breweries. Below we explain what we think is going on, and offer some strategic advice for craft breweries going forward.

Note: We have not spoken to anyone in the companies mentioned below. Our review of publicly available data, plus some thinking about how industry growth occurs outside of beer and which parts of a generic industry growth strategy fit and do not fit the current US craft beer industry. Also, we include formerly “craft” breweries like Founders and Lagunitas in our analysis, actually they are the heart of our argument. Our definition of “craft” includes all former craft breweries that are now corporate owned – because small craft breweries compete with them head to head, everyday.

Read all the way to the bottom if you want to know one way that the craft beer market share could grow significantly beyond the BA’s 2014 prediction of 20% of total US beer market. Read all the way to the bottom if you believe premiumization and taproom/at brewery sales are the only good strategy for every craft brewery – we believe you would be wrong. Don’t blindly trust the consumers/sales data immediately in front of you, take 5 minutes and keep reading to understand how different customer groups respond to different marketing tactics. Don’t blindly trust the BA reports that don’t include former craft breweries like Founders and Lagunitas; to the majority of beer drinkers (the early and late majority customer segments) they do count as craft. Read below how this works and then decide where you fit.

Is there still a place for a “flagship” driven beer business strategy?

It seems that breweries like Founders and Lagunitas are “buying market share” or at least they are focused much more on volume growth than most small craft breweries that are (wisely) focused on dollar growth. How does this make sense? We believe it is because (the deep pockets of) a few large European Brewers are relying on a flagship model for success. Didn’t the flagship model go out of fashion with craft beer enthusiasts? Yes. Aren’t companies like Craft Brew Alliance struggling with their former flagship strategies like Widmer Hefeweizen? Yes. Why would a European Brewery still use this strategy in the USA? It is because they are competing for different customers. We believe two EU Breweries in particular, Heineken (Lagunitas) and Mahou San Miguel (Founders) are strategically positioning themselves to win the early and late majority segments of the overall US beer industry.

This matters because adoption by early and late majority consumers will (theoretically at least) skyrocket craft beer’s influence “across the chasm” (Moore, 1991) and could grow overall craft market share from the current range of 10%-17% toward as much as 70% of the American beer market. These European companies know how to win a market share game, and they aren’t using “crafty” beers like Blue Moon or ShockTop to do it. Further, they aren’t buying up multiple craft brands in a variety of regions like AB InBev has done. They have a “one-brand-one-flagship” model, and they are laser focused on getting beer drinkers like my dad and my uncle to pick Lagunitas IPA or Solid Gold Lager instead of picking from a great local nano- or microbrewery. When early and late majority consumers (like our dads and uncles) contemplate rotating tap handles at brewpubs and bars, or packed shelves at grocery and convenience stores, they make their choices differently from earlier adopters and craft beer enthusiasts. These European brewers with years of acquired marketing wisdom know this about the early and late majority, and they know how to exploit the difference.

Founders and Lagunitas are playing the same game with different strategies

As detailed on Brewbound in late 2017, Founders has seen enormous growth at a time when most regional craft breweries are flat or down. According to Forbes,much of this growth can be attributed to aggressive (or downright low) pricing across their portfolio of off-premise 15 packs. For example, as stated in the Forbes article, Founders recommends Solid Gold Lager be priced at $1.17 for 12-ounces versus the craft national average (According to IRI) of $1.56 per 12-ounces. This means Solid Gold six packs are more in line with Budweiser 6-pack prices than most craft brands. In some ways, Founders appears to be buying market share, trading volume growth for dollar growth. This goes opposite to the premiumization trendand price increase occurring in most taprooms and among the USA’s smallest 6,500 breweries. What could be driving this strategy? Hold that thought for a minute…

At the same time that Founders is seemingly buying market share, Lagunitas is growing while charging a super-premium. Lagunitas CEO Maria Stipp told Brewboundthat mid-2018 sales were up 4% in dollar growth and 5% volume growth. However, unlike Founders’ low cost strategies, Heineken owned Lagunitas has among the higher priced offerings: at an off-premise case price of $38.37, they are the seventh highest price among nationally available craft portfolios. Lagunitas remains highly focused on their flagship IPA, which ranks #1 in the IPA category in the USA. We note that Heineken recently went through a big layoff of sales people at Lagunitas, but their strategy remains a one-flagship-premium price winner. What does this all mean?

We think that the European ownership of these national craft brands tells an interesting story. Back in 2014, we predicted that Heineken would have an aggressive craft beer acquisition strategy that matched its flagship model of promoting their signature Heineken Pilsner. Unfortunately for them, the Heineken as “aspirational” brand tactic no longer works as well in the context of the super-premium craft beer movement. Since 2014, we have seen Heineken buy up Lagunitas Brewing and similarly position it as a flagship model, infusing the company with money and growing Lagunitas’ sales globally. Similarly, Founder’s Brewing is partially owned (30%) by Spanish brewer Mahou San Miguel. At the time of the minority investment, Founders Brewing’s blog offered the following glimpse at a global flagship strategy for Founders: “Mahou will help us grow to be an internationally recognized brand. They’re looking at this investment as a long-term partnership, and they’re excited to help grow Founders throughout their extensive global distribution footprint.”

To summarize, these European owned and European influenced American craft breweries are using a flagship model that has fallen increasingly out of favor among most small American craft breweries. Further, while AB InBev appears to be competing with the small US craft brewers in a fight for enthusiasts and early adopters (only 15% of beer drinkers), Heineken and Mahou San Miguel are fighting for the other 85% of American beer drinkers with a flagship craft strategy – and it is working. Keep reading for a quick lesson on the laws of innovation diffusion and industry growth.

Flagships are dead! Long Live the Flagships!

We believe the increasing reliance upon a flagship model is highly correlated with an increase in foreign ownership of these companies. Further, we think these foreign owners aren’t as tied to being “craft” or to being “American craft” and we think this is smart for attracting the early and late majority of beer drinkers.These foreign owners are chasing volume and sales markets (dominated by the classic American premiums, like Budweiser, Bud Light, Miller Lite, Coors, and Corona Extra drinkers). However, instead of building “crafty” “or craft-ish” brands like Blue Moon or Shock Top, these European owners are taking aim at the early majority with some of our best legacy craft breweries and nationally recognized craft brands.

Our argument rests on two well-documented industry strategy frameworks: the industry lifecycle and innovation diffusion (Rogers 1976; Rogers 1983), plus an understanding of a particular component within those frameworks that is called “the chasm” (Geoffrey Moore, 1991).

Let’s start by making a general assumption: all growth industries need adoption by the early majority market. The only time this is not true is if the industry has no desire or drive to grow beyond at most 20% of the potential market for its goods or services. This is the core strategy of Founders and Lagunitas – let all of us small craft breweries continue to fight over the 15-20% of “true craft drinkers” while they gobble up market share and push into the early majority. Figure 1 (below) depicts a generic innovation diffusion scenario.

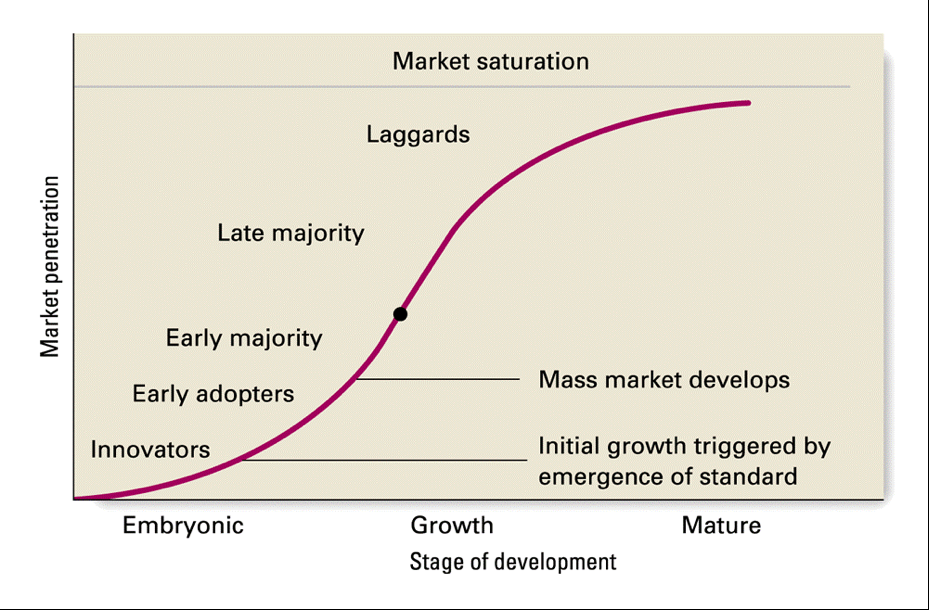

Figure 1 offers a graph of the generic innovation diffusion situation (Rogers 1976; Rogers 1983)

The first two groups to adopt a new offering are the innovators and early adopters. As the growth stage hits, two very different groups must get involved for mass market development, the early and the late majority. However, the transition from initial growth to mass market adoption often does not occur. There is a “chasm” that often does not get crossed. There are many reasons that make it difficult to “cross the chasm.” The foremost reason is the vast difference between the needs/desires of the majority versus the innovators and early adopter types. Industries get stuck because they have become accustomed and bound to serving the innovators and early adopters that loyally helped carry the industry through the embryonic and early growth stages of its development.

Sound familiar? It should, because loyal, enthusiastic and knowledgeable craft beer drinkers by far dominate the market segment that currently purchases craft beer. Craft breweries have become experts at pleasing this group, and have developed a joint loyalty. This is not a bad thing, it just leads them to having less focus on the majority of beer drinkers than would be ideal.

According to Geoffry Moore (1991), innovators are “enthusiasts,” they like to be first and they are willing to put up with inconsistencies and to tinker with early versions of a technology, a product or a service. Early adopters are “visionaries” who explore the new innovation and envision modifications that could bring the innovation into the main stream. They like special treatment and will put up with trial and error. Both innovators and early adopters like to experiment and are ok when quality is not always there, and ok with purchasing a brand or style they are unfamiliar with. But these folks only account for 6-16 percent of the market. These are the “true craft” drinkers most of us are competing for.

Lagunitas and Founders are playing a different game – they want to own the early majority.

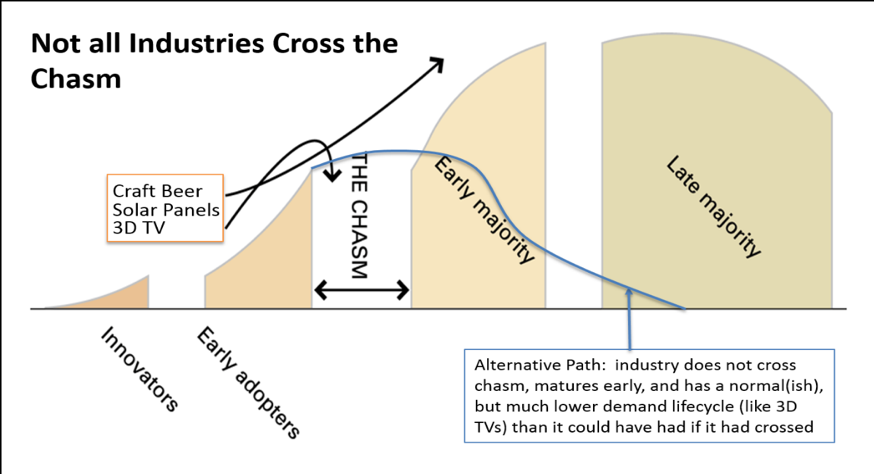

The early majority and the late majority are very different from early adopters and innovators (see Figure 2 below). An industry that does not understand the differences enough to also appeal to the idiosyncrasies of the early majority has greatly reduced chances of crossing the chasm to mass adoption.

- The Early Majority does not like trial and error

- The Early Majority are pragmatists

- The Early Majority knows what they want and need

- The Early Majority does not want to make extra effort to find it or acquire it.

- The Early Majority won’t try something unless someone else has tried it first.

- The Early Majority wants it to be available and convenient

- The Early Majority is willing to pay fairly for if it gets what it wants and needs

- The Late Majority is conservative

- The Late Majority accepts a new way only when the old way is no longer viable

- The Late Majority expects low prices and high customization (that it don’t like to pay for)

- The Late Majority expects the most convenient acquisition possible

Figure 2 highlights the "chasm" that must be crossed to reach the early and late majorities (Moore, 1991)

All of this together means that If craft breweries want to cross the chasm and gain adoption by the early majority, (which accounts for about 24% of market share) and then the late majority, (which accounts for 45% more of the market), then craft breweries will have to provide broadly available, consistent quality, broadly distributed, branded beers. In a word: Flagships.

Brands like Founders and Lagunitas are the poster children for craft to cross the chasm. My father (a typical early majority member) orders All Day IPA when he goes out. My uncle orders Lagunitas IPA. Those are “their” beers now, and for them, this is completely craft beer. These brands are what the early majority are ordering. Because they taste good? Yes. But just as importantly, because it can become a “my beer,” because consumers can get it everywhere, at least in their super-region.

This is where Founders and Lagunitas are focused… and if they win to some extent we all win as the overall market share of craft can achieve more than 50%. After all a rising tide floats all boats, right? At the same time, this feels like a somewhat unsatisfying result. Why should non corporate sponsored craft breweries leave this giant slice of market share to the foreign owned behemoths?

So what should a craft brewery do? Don’t get stuck in the middle

Most craft breweries need to do nothing. Small local sales strategies will not need to change all that much. Many microbreweries can survive on innovators and early adopters. However, most important for the craft beer group is that a strong handful of regional breweries emerge and also pursue the flagship model on a regional or even national level. The challenge is that a lot of large regional producers are “stuck in the middle”. Sam Adams, Sierra Nevada, New Belgium, Bell’s, and breweries like these are in a tough spot. They are trying to appeal to enthusiasts and the early majority – and they don’t have as deep of pockets as Heineken does. Yeungling is much closer to a flagship model and less stuck in the middle among the largest US craft breweries.

If you are a brewpub, nanobrewery, or microbrewery selling most of your beer direct to consumers – keep doing that! Craft brewers under 40,000 barrels annual production should definitely continue to provide variety, one-offs and other experimental brews in their local markets in their tasting rooms and brewpubs. However, if you want to grow and get big, we believe you need to choose a flagship, but don’t make it yourself. We foresee a lot of flagship beers being brewed by friends in the sharing economy.

Flagship Strategies for Small Craft Breweries: Using the Sharing Economy

While we do see the necessity of the flagship model to get craft across the chasm, we do not recommend spending money on huge new tanks (until it is absolutely necessary) in order to make this scaling up possible. Instead we encourage brewers to contract brew with reliable high quality brewers, creating a well-dispersed production and distribution network that can cover a region while utilizing existing excess capacity. Crafting a Strategy members are already doing this between the USA and Europe.The key is getting just one flagship beer consistently brewed, packed and delivered in all cities all over your region. With one beer, like Occidental Kölsch, Melvin Killer Bees Blonde, or Backwoods Copperline Amber, who knows what could happen with passion, hard work, a shared economy production network and the vision that so that these beers could be ordered pretty much everywhere.

REFERENCES

Moore, G. A. 1991. Crossing the chasm: Marketing and selling high-tech products to mainstream customers (Collins business essentials). HarperBusiness, New York

Rogers, E. M. 1976. New product adoption and diffusion. Journal of consumer Research, 2(4): 290-301

Rogers, E. M. 1983. Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press