Sam Holloway, Ph.D. - Crafting A Strategy

Many smart business people are studying the craft beer industry and conducting high-level analysis on brands, their messages, and the efficacy of advertising. Here is a recent article from a good blog we follow, TheDrinksBusiness.com

Their analysis hits upon a problem for breweries in an increasingly crowded market: If our messages are all the same, how can we differentiate our brands?

What kinds of messages should we send to consumers?

It is easy for most of us to use hindsight to recognize a valuable brand. Apple has an iconic brand; Sam Adams has Boston Lager, embodied by the vision of founder Jim Koch smelling his beer in their wonderful advertisements. For larger breweries with vast financial resources, creating advertisements is an exciting and very effective way to communicate their brands to consumers and drive that emotional connection that leads to sales. What about the rest of us? If we don’t have the financial resources and have not yet fully developed our brands, how do we communicate with customers in a way that will form an emotional connection that leads to a transaction?

“Marketing has always been about the transaction” according to CRAFTINGASTRATEGY.COM Expert Blogger, Dr. Peter Whalen [1]. In his Members-Only blog, Dr. Whalen continues: “It is vitally important for brewery owners to consider the exchange process before it begins to make marketing decisions…Don’t think of it as exchange value (what the consumer is willing to pay), think of it as use value, what benefits do they derive from consuming the beer. Use value unlocks the emotional and psychological costs and benefits that will allow you to create, deliver, communicate and, ultimately, exchange value with your customers.”

How do customers derive use valuefrom products like Beer?

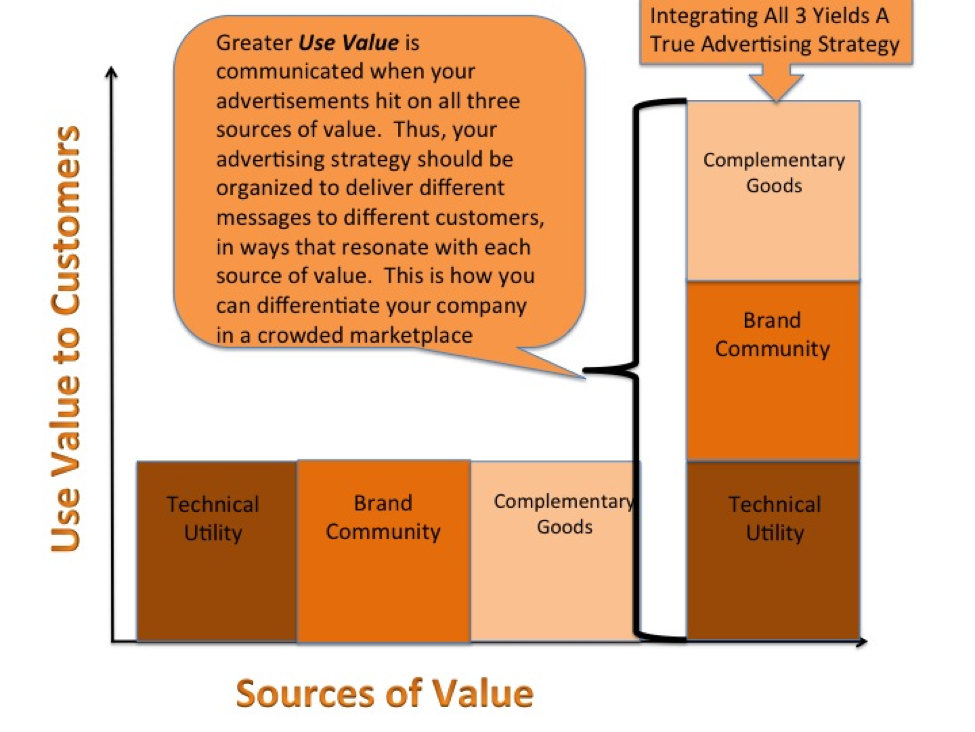

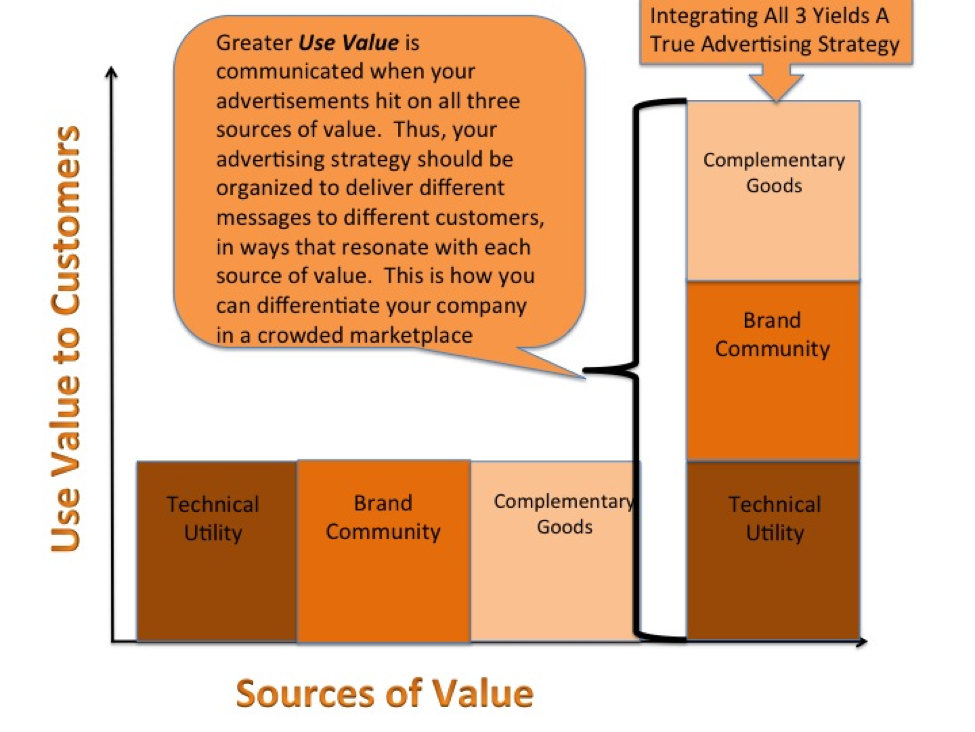

We really like the research of NYU Professor, Melissa Schilling. Schilling suggests that a product can convey value to a customer in one of three ways. First, there is the technical utility the product offers to a customer. Technical refers to what the product actually does for a customer, and utility is a word for how much value the customer receives from using that product. For beer makers, the technical utility is the quality of the beer, its aroma, flavor, mouth feel, etc. Packaging the beer well, keeping it refrigerated and serving it fresh also enhance the technical utility.

Schilling says the second way for a product to deliver value to a customer is through the product’s “installed base.” The installed base is the total number of placed units of a particular product within the entire market or product segment. For Apple’s iPhone, the installed base is how many other people have an iPhone. iPhone users can text or Facetime with each other for free. So the more iPhone users there are, the more people iPhone users can call for free. Plus there is another benefit. The more utility each user gets, the more new people want to join in and get an iPhone too. This is a rich-get-richer-cycle, technically called “increasing returns to adoption” or “preferential attachment.”

For beer companies, think of your installed base as the total number of product placements and end users in every geographic region where your beer is bought and sold. In each of these locations, people will interact with your beer, interact with each other while they drink your beer, and the more people interacting and drinking your beer, the greater value your company delivers to its installed base. All those distributors, bartenders, servers and beer drinkers speak of the utility of your beer as they drink it. Your job is to give customers and partners positive things to talk about and share that other people like talking about and sharing too. This will cause outsiders to want to join your community.

“I’ve met the Brewmaster, she is awesome and really seems to care about quality…Have you been to their tasting room and met the staff? They all seem to really care about each other and the quality of the beers.”

“They put their beers in cans because it protects the beer better and keeps it fresher, plus it is really easy to take camping; want to go camping with us?”

Your advertising messages to the installed base must leverage your Brand Community. A Brand Community is a web of relationships among customers, marketers, the product and the brand. These relationships are characterized by a sense of community and belonging, shared rituals, practices and places, a moral obligation to the brand and fierce loyalty to the brand (McAlexander, Schouten, & Koenig, 2002). Thus, when designing your messages, it is not simply enough to tout how great your beer tastes. You need messages that enrich the brand community and leverage the fierce loyalty among community members. As reported in TheDrinksBusiness.com blog, attempts to communicate with a brand community end up as messages like: Our craft beer brand is all about…“real people”/ from a nice place/ believing in their beer/ having fun brewing beers/ using good wholesome ingredients (while caring for the planet). (Fox, 2014)

The third way that a product creates value is through the availability of complementary goods for that product. Apple’s iPhone is a wonderful product with even better complementary goods. These complementary goods include the iTunes store, the App Store, Macintosh computers, AppleTV and a host of other goods whose value and connectivity increase the value of being an iPhone owner. What are the complementary goods to a craft beer product? Ask yourself this question: How does consuming my beer enhance the value of other items associated with the quality of my beer and the core members of my brand community? Merchandise, such as T-shirts, hats, glassware, growlers and coasters allow a consumer to take a piece of your story with them, and share it with others. These are certainly complementary goods. Has your beer been featured in a book, such as The Beer Goddess, Lisa Morrison’s (2011) book on craft beers of the Pacific NW? Your brand gains surplus value from being mentioned in this type of complementary good. Does your distributor put your logo on their trucks, to showcase your brand as they deliver beers to distant neighborhoods? Do you have a tasting room where consumers can congregate and celebrate your quality beers and also each other? Each of these complementary goods enhances the overall value a consumer gets from your craft beer products. Using all three sources of value simultaneously (bringing it all together) yields dramatically more use value, which our chart below shows.

Bringing it All Together: Developing Distinct Messages to Each of Three Sources of Value

Do you really have an advertising strategy?

By designing your messages to hit all three sources of value, you begin to make the leap from marketing novice to marketing strategist. With limited resources and even less experience, many craft brewery owners are overwhelmed and end up ignoring any strategic thinking in favor of a Facebook page, a Twitter handle, and blasting any and all messages to anyone that will listen. While this might work for a while, as the industry keeps getting more crowded, breweries will need solutions that facilitate transactions. After all, that is what marketing is supposed to do.

My next blog will suggest which communication channels relate to each of the three sources of value. Should Twitter messages aim to evangelize your brand community? Or are Twitter messages better used for things like scheduling, announcing new events, and pictures? Since Twitter is amazing at scaling and getting your message to as many people as possible, and also facilitates brand community members sharing with each other; the Twitter communication channel is aligned with “increasing returns to adoption”, which we associate with the ‘installed base.’ Thus, Twitter messages should be aimed at the installed base primarily, and at the other sources of value in a secondary role… This is the kind of strategic advertising thinking that allows you to engender use value at a fraction of the cost of hiring a professional advertising firm. My next blog will align each communication channel (Twitter, Facebook, etc.) with its highest impact source of value…

What about videos of your brewmaster introducing your latest and greatest barrel aged beer? Is video the best medium to communicate your beer’s technical utility, or would a press release about a medal you just won be a better way to reach more people? How can you organize your messages and deliver them effectively and efficiently? Stay tuned or consider membership at CRAFTINGASTRATEGY.COM. Our members are currently discussing these important topics through our forum and through commenting on our White Papers. We would love you to join us and enhance our learning community.

References

Fox, D. 2014. Craft-Beer: One Strategy Won't Fit All, TheDrinksBusiness, Vol. 2014: Anthony Hawser.

McAlexander, J. H., Schouten, J. W., & Koenig, H. F. 2002. Building Brand Community. Journal of Marketing, 66(1): 38-54.

Morrison, L. M. 2011. Craft Beers of the Pacific Northwest: A Beer Lover's Guide to Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia: Timber Press.

[1] Dr. Peter Whalen is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the University of Denver. His academic research is focused on the interface of marketing and entrepreneurship and has been published in Harvard Business Review blogs, Huffington Post and various international academic journals.